I had the opportunity to be an early reader of the galleys of Who By Fire by Mary L. Tabor. An excerpt from my review appears at the end of this essay.

What do you take with your morning coffee? What do you see in the domestic details of your life? Ours is an object-world that we give scant attention. Heads down, little eye contact as we walk along city sidewalks, or scenery flickers past while jogging, or driving down a country road while listening to the news. How do your morning habits shape the perception of your day?

These questions came to mind as I reread one of my favorite essays, Sam Pickering’s “The Breakfast Table.” Pickering, a retired professor of English at the University of Connecticut, writes;

For decades reading the newspaper at breakfast nauseated me. A glance at the contents, and my mood turned to dun while bile began to percolate, its grounds rough and almost tiny, as if my feelings were being shoveled into a burr mill. That has changed. A month ago, I canceled my subscription to the morning paper. Now at breakfast, I sip a cordial of poetry.

Morning habits have varied for me over the years. The one constant is the pleasure I take in the quiet with a cup of coffee. Mornings are when I am setting myself in order to do my creative work—the thinking hours.

Before leaving home for college and lives of their own, there were breakfasts and school lunches to prepare for my children; cereal was served only on Fridays. During the summer months, I took them to a lake for swimming and a picnic, and home by two or three in the afternoon for a couple of hours of schoolwork to maintain their skills, and for nature walks. For years, I listened to either National Public Radio’s Morning Edition or the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s shows. I read The New York Times. Course requirements to meet as a student, then, in later years, employment, both in business and academia. This was followed by the years of research, writing, meetings, teaching, and other obligations. There were mornings when I took long walks along the Huron River, across a meadow, or through the woods, or along city streets. Then there were years when summer mornings became a time for tending the kitchen garden, mowing, and other yard chores. Later, Tim Hortons became my stop for a cup of coffee, to people-watch, converse with strangers, and read. Despite time constraints, I tried to squeeze in quiet moments with poetry or essays that offer unconventional truths, pausing to appreciate the beauty of the writer’s use of language.

Over the past few years, I have read The New York Times, the Wellsville Sun, and CBC News. Perhaps it would be more truthful to say that I peruse the news in the morning, returning to it in the afternoon for thorough reading. This strategy of avoidance of in-depth reading helps me perceive what is good and beautiful in our fractured world, which is in need of healing.

I found my attention drawn to Henry David Thoreau’s essay “Walking” while I reread Pickering’s. Just as with Pickering, I often return to Thoreau’s essay in which he notes:

We have heard of a Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. It is said that knowledge is power; and the like. Methinks there is an equal need of a Society for the Diffusion of Useful Ignorance, what we call Beautiful Knowledge, a knowledge useful in a higher sense: for what is most of our boasted so-called knowledge but conceit that we know something, which robs us of the advantage of our actual ignorance? What we call knowledge is often our positive ignorance; ignorance our negative knowledge.

We read and listen to the news, accumulate facts, and develop attitudes. There is a literal bombardment of demands competing for our attention. The relentless noise is similar to hearing a commercial jingle that continuously plays in our minds. But, are we cultivating ourselves? Do we take the time to think and feel, to address our “negative knowledge?” This isn’t to say we should ignore world events, but rather to ask if we should allow the endless news cycle to limit our vision, prevent us from thinking and considering that, in the words of Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poem “The Lotus-eaters”:

There is sweet music here that softer falls/ Than petals from blown roses on the grass

In our busyness, do we take the time to listen to that sweet music? Pickering reminds us that poetry directs our attention from what is trumpeted as imperative, vanishing it from the morning, so one’s perspective changes. Poetry cultivates a sensitivity to the magic of words, language, and how their potential for interaction creates a visual of emotions and the environment we encounter daily, but too often fail to see. Poetry, like literary works, is a creation of images, word pictures. The poet Ellen Bryant Voigt reminds us that the “picture in words,” in the “discursive system of language, (is) the body ‘thinking’ through its senses, the mind embodied― which reflects the paradox of human consciousness: the fact that the mind is body, whether sense organs or cerebrum.”

A poem is a snapshot of an ordinary moment that is worth remembering. The poet is aware of her response, unmasking the inner and outer values of relationships to understand the truth she tells. The use of the personal, first-person “I” can be misleading. Sometimes it is the poet. Other times, it is a character. Often, particularly in modern and contemporary poetry, it isn’t easy to make the distinction. In either context, what is essential for the reader to understand is that the poet is attempting to clarify a moment of life in a structured manner that is ultimately an invitation for us to gain a different perspective that is useful to our lives. As a form of communication, poetry works when it doesn’t favor abstraction or preaching with claims of objectivity. Such poems are pretentious and unconvincing.

We tend to think of poetry and shrug it off as either a form of communication for the young who are learning to express their thoughts and emotions or for the intelligentsia. As W.H. Auden observes, “We are accustomed to a culture in which poetry is the highbrow medium, to be employed for communicating the most intense and subtle experiences, while the medium for everyday use is prose, that it is difficult for us to imagine a society [i.e., before 1300] in which the relative positions were the other way around, a time when verse was the popular medium for instruction and entertainment and prose, mostly Latin, the specialized medium for the intercourse of scholars.”

Our morning hours are winged, they fly off, but can be the most gratifying, shaping our attitudes and perspective for the new day. The words we hear or read stay with us, and open eyes see the unexpected even in what we are acquainted with in our social roles and environment. Poetry isn’t a cure-all for what is ugly and corrupt in society. Instead, it adds texture to our lives. As “Beautiful Knowledge,” poetry makes us more sensitive, observant, and more fully alive to others and the natural world we live on the edge of and race past. We require periods of thoughtful silence to understand ourselves better. In thoughtful silence, we momentarily set aside the drama all around us. As Robert Haas writes in his poem “Iowa City: Early April”:

All this life going on about my life, or living a life about all this life going on,/ Being a creature, whatever my drama of the moment, at the edge of the/ raccoon’s world—

One morning, when your position in the queue for coffee (and a pastry) ends with you at the counter, or the drive-through window, order a poem with your coffee. Then find a quiet place for a few minutes of respite at the edge of the morning rush.

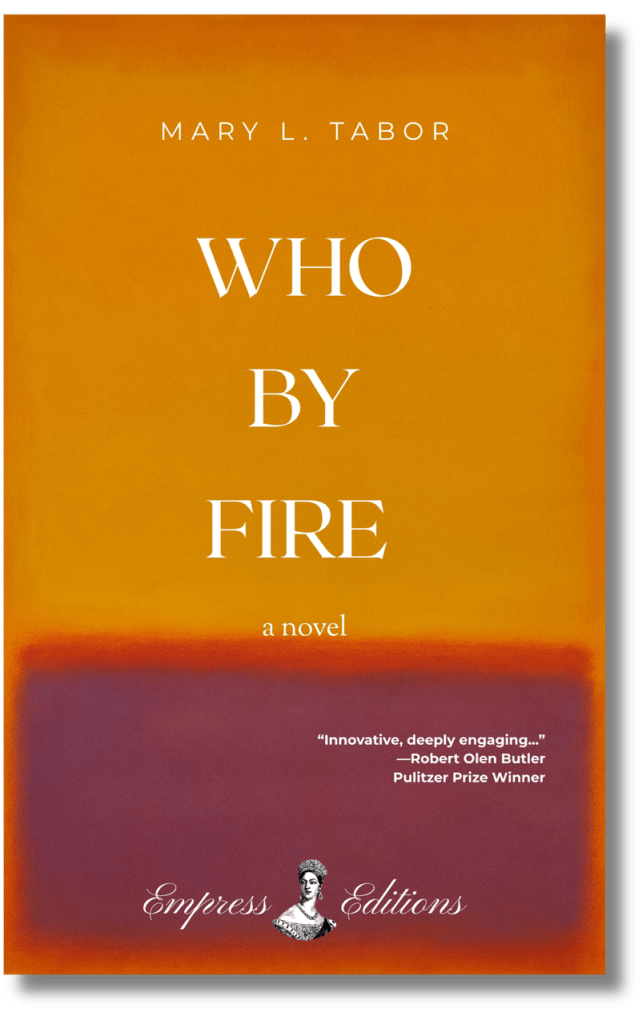

The following is an excerpt from my review of Mary L. Tabor’s book.

Who By Fire is an engaging, beautifully written novel by Mary L. Tabor. This is a well-written, sensual, tender, poignant, and intelligent love story about family, friendship, faithfulness, betrayal, and healing, told in lyrical prose. She brings a freshness to the age-old theme of adultery with the assurance of a writer in complete control of her craft. This compelling and innovative novel will be one you remember and want to return to for its richly layered perceptions of how human beings navigate their complex relationships.

Who By Fire, available for pre-order on Amazon, Barnes and Noble and Book Shop, a re-issue by Empress Editions via Hachette. The book, available as a paperback and ebook, will be released on 24 February 2026.

Poetry and Standing at the Edge of the Raccoon World first appeared on https://marytabor.substack.com/. I encourage you to subscribe to her site for essays on books, the arts, and the writing life.

Flowers from Rock © 2026 Charles van Heck

Poetry and Standing at the Edge of the Raccoon World © 2026 Charles van Heck

Leave a reply to Charles van Heck Cancel reply