A friend, Eszter, invited my wife and I to breakfast at the Dexter Brunch House this past Sunday. The ambiance is comfortable and modern, and the cuisine is good. The restaurant has undergone numerous changes to its name and interior design over the years. When I first went there, it was known as The Lighthouse. Then new owners changed the name to the Dexter Riverview Cafe, which seemed more appropriate given its proximity to a river navigable only by canoes or kayaks, if that. No lighthouse needed. The restaurant changed hands. Owners came and went for various reasons. Eszter’s husband, George, and I dined at the restaurant when it was a Koney Island. A Koney Island, for the uninitiated, is this area’s idea of a diner. I must acknowledge my prejudice. My idea of a diner is The Randolph Diner Bar & Grill in Randolph, New Jersey, and the Oakland Diner in Oakland, New Jersey. Show me the directions to a good, authentic Japanese or Mexican restaurant or a kosher deli, and I am on my way.

In the early days of our marriage, Terri and I would pick up the Sunday New York Times and go to a place called Bagel Nosh in Southfield, Michigan. Kosher. A bagel with lox and onions was my breakfast of choice. This meant Terri avoided kissing me for the rest of the day, so much for the early days of marital bliss. Despite Terri’s aversion to this perfect Jewish culinary staple, our marriage has survived forty-six years.

I consider meals to be a sacred time set apart (kadosh), sacramental, partaking of the offering of the earth, those gifts of God, and the labor of women and men, provided for our nourishment. I base my understanding of a meal as sacramental on the Greek roots for gift-giving: eu + kharistia (eucharist), which can be translatedas “thanks-giving” or “giving blessed gifts.” The quality of the meal is important, a gift offering to those present, but more important is the gift of the participants to one another.

Meals with family and friends are the most enjoyable. Throughout our marriage, until recent years, our table was shared with friends and acquaintances from various countries, different races and creeds, with diverse careers and interests. The conversations were engaging, covering a broad range of topics. I recall a colleague asking me when he would be invited to one of our Sunday dinners. “I hear your home is the place to be invited to.” We quickly remedied the situation: friends and friendship.

The word “friend” is used rather lightly in our daily interactions, particularly in associations formed on social media. Our use raises the question of what the word “friend” means and what it implies for our relationships.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines friend as “One joined to another in mutual benevolence and intimacy.” The first known use of the word in the English language is found in the poem Beowulf. Herorot innan wæs freondum afylled. The Old English literary and linguistic scholar J.R. Tolkien, and here I will add his additional words to the verse for insight, translated the line as: In this place is each good man to his fellow, true, friendly in heart, loyal…

The British philosopher Thomas Hobbes, with whom I mostly disagree, captures my sentiments towards friends: “A friend is he that loves, and he that is beloved.”

Love, the bond of affection that unites people together in friendship, is multi-layered. Confidence, trust, loyalty, mutual respect, and having common interests are foundational. There is another layer, one often overlooked, that contributes to the bond- enough uncommon ground to keep things interesting. The uncommon ground is what allows us to learn from one another. These elements require goodwill for a friendship to work. The Roman lawyer, orator, and philosopher Cicero reminds us that goodwill is the repose of friendship:

…in friendship there is nothing false, nothing pretended; whatever there is is genuine and comes of its own accord…. Friendship springs rather from nature than from need, and from inclination of the soul joined with a feeling of love rather than calculation of how much profit the friendship is likely to afford.

We will have our inequalities (talents and skills), but in friendship, there is no superiority or inferiority. We stand as equals, respecting one another’s dignity even when we annoy one another. In friendship, loyalty comes from an open heart.

Euripides asks, “When Fortune smiles on us, what need of friends?” Fortune doesn’t always smile. Aristotle argues that friendship is necessary throughout a person’s life. He writes in The Nicomachean Ethics:

Friends are indeed a help both to the young, in keeping them from mistakes; and to the old, in caring for them and doing for them what through frailty they cannot do for themselves; and to those in the prime of life, by enabling to out fine achievements: ‘When two together go’ (Homer, Iliad 10.224) they are better able to both see an opportunity and to take it.

In his The Guide of the Perplexed, the Medieval Jewish philosopher Maimonides quotes Aristotle when discussing the role of mutual love and assistance among the people united by the Covenant.

There are three types of friendship according to Aristotle. First, a friendship based on utility, which is a relationship based on mutual usefulness, an advantage to be found with another person. This is typically found in business and political relationships. The second, which is usually found among the young, is based on pleasure, on taste, feelings, emotions, and interests. When we are young, we fall in and out of love as our attitudes, emotions, and interests shift, often rather quickly. The third category of friendship is based on goodness (virtue) —what is good for ourselves and the other—a relationship based on a similarity of interests, feelings, and care. We value the other because they value us in mutual respect. There is a melody of tones, if you will, that seeks to love more than to be loved— to give rather than receive. True friendship breaks our hardness of heart, our self-centeredness. The author David Brooks observes:

Self-centeredness leads in several unfortunate directions. It leads to selfishness, the desire to use other people as a means to get things for yourself. It also leads to pride, the desire to see yourself as superior to everybody else. It leads to a capacity to ignore and rationalize your own imperfections and inflate your virtues. As we go through life, most of us are constantly comparing and constantly finding ourselves slightly better than other people— more virtuous, with better judgment, with better taste. We’re constantly seeking recognition and painfully sensitive to any snub or insult to the status we have earned for ourselves.

Cicero and Brooks use the word “virtue” when writing about friendship. In Latin, vitūs, in their context of usage, means goodness, moral perfection, high character, worth, merit, and value. Virtue is, to my thinking, what we ascend towards, or, to put it differently, we cultivate and develop. Virtue is a person’s stature, their character of integrity. The Hebrew word middot means measure, but is usually translated as “character traits,” the measure of a person. Mussar refers to moral conduct, instruction, and discipline in Hebrew. We are always, or should be, striving towards being our better selves.

For the most part, we become acquainted with others; those people enter our lives and leave at different times. We are misled by the various forms of social media, the “number” of followers, with whom we become “acquainted” based on their posts. True friendships, the lasting ones, are difficult to find, but the most rewarding. In true friendships, we discover our better selves through the openness of heart.

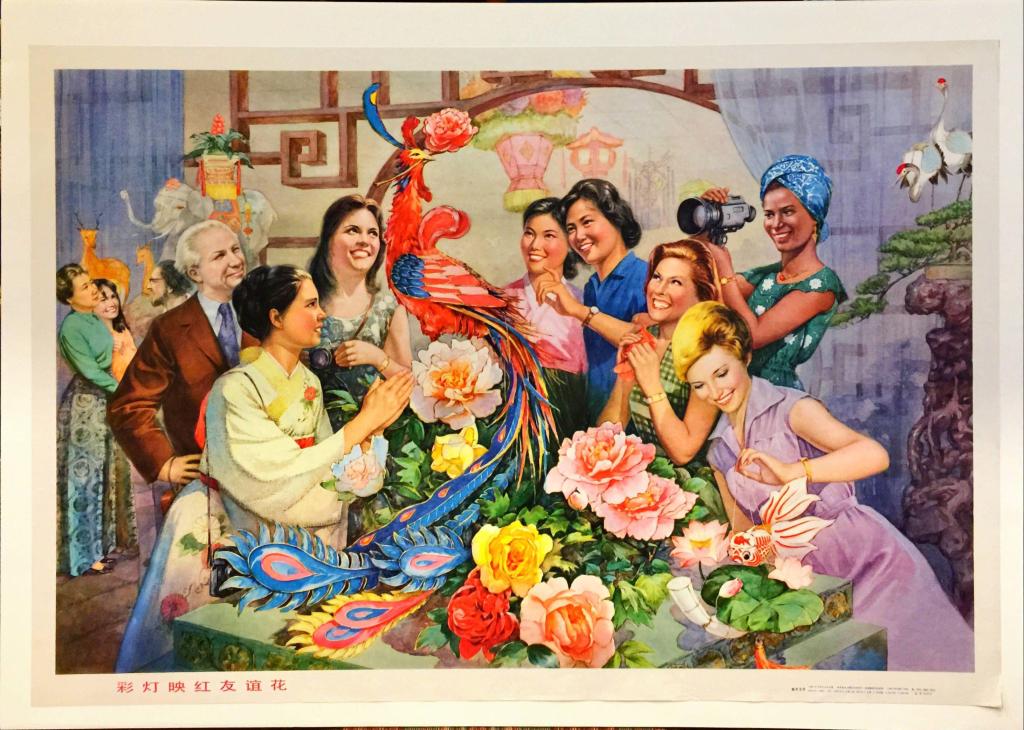

Image:

Artist: Creator Yao, Zhongyu (姚中玉)

Title: 彩灯映红友谊花 = Colorful lamps light the flowers of friendship

Source: The Claremont Colleges Digital Library (CCDL)

[Lithograph?], 30.75 in x 20.75 inches; Len Rubenstein Chinese Political poster collection, Special Collections, The Claremont Colleges Library

Leave a comment