The decision was made. There was a lesson to be learned. The suitcases were packed, and placed in the car. In the early hours of a July morning, my father backed the car out of the garage. We were going South into Jim Crow country.

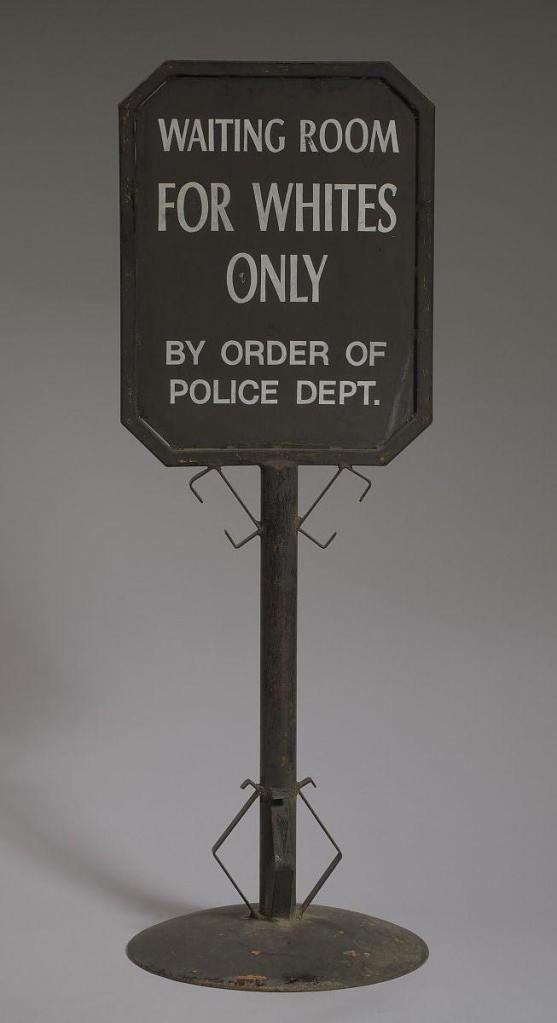

What exactly does Jim Crow mean? The laws and etiquette of Jim Crow are complex. They were established to maintain White supremacy over Black people in politics and daily life. We associate Jim Crow laws with the disenfranchisement and suppression of the Black vote in the Deep South. Etiquette is a matter overlooked, unless you were perforce compelled to live by the rules. The rules governed social interaction from shaking hands to how Black people were to be introduced. Black people were introduced to a white person by their given name, and a Black person never introduced a white person. Whites were addressed by their title, Mr., Mrs., or Miss, Sir, Ma’am to show respect. Black people were denied this. They were forbidden to show public affection to one another. Vehicles driven by whites had the right of way at intersections.

There are numerous other rules of etiquette that governed the Jim Crow South. This was the South that my father wanted us to see first hand 64 years ago, 100 years after the start of the American Civil War.

I recall the Whites Only drinking fountains, bathrooms, and inequality of service at restaurants. We drove past the homes of farmers working leased land. The most striking contrast was Washington, D.C., that marble city of monuments and buildings. One evening, lights shone gloriously on the Jefferson Memorial, Washington Monument, Capitol Building, the White House, and other buildings. “A City on a Hill,” came to mind. The following day we went into the area tourists avoid. Driving east of the Anacostia River, we entered Wards 7 and 8. Congress Heights. The economic and political disparities, the sharp contrast, was something my father wanted us to see.

My mother told me a story; one she was unable to forget. She was in her bedroom on the family farm in Allentown, New York. As she lay in bed, she glanced out the window, then rose for a better look. The scene terrified her. On a distant hill, my mother saw a large cross burning. Northerners are subtle in their racism. We prefer to forget the activities of the Ku Klux Klan in New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and New England during the 1920s and 1930s. There were 11,000 members of KKK in Albany, for example. The Klans influence waned as an organization, but many of the racial prejudices remained, slithering along like a snake towards its prey.

In his book Angels in the Architecture, Douglas Wilson writes: “When the Confederate States of America surrendered at Appomattox, the last nation of the older order fell. So, because historians like to have set dates on which to hang their hats, we may say the first Christendom died there, in 1865. The American South was the last nation of the first Christendom.”

What does Christian Nationalism actually stand for? First, we need to understand that it is not merely a Southern phenomenon rooted in Protestant evangelism. Christian nationalists resides in all 50 states. Second, though some members will cloak themselves in either the Confederate battle flag, or the “Appeal to Heaven” flag, the American flag is the primary choice. Christian Nationalist adherents think of themselves as patriots. Third, according to a Brookings Institute survey, 40% of the adherents think that resorting to violence to save the nation is acceptable. “White supremacy is alive and well in the U.S. and appears to be using violence and intimidation to shape a conservative political agenda.” Fourth, racism underlays the ideology of this “faith,” connecting it to and promoting white supremacy. Fifth,the movement is grievance driven, a sense, real or imagined, of insecurity, and discontentment. The target of blame becomes “the other” be they racial minorities, women, Jews, and others who are different in their value systems (e.g. the LGBT community). Those in the political, and too often in religious leadership take advantage of this to cultivate the grievances for their personal power and economic gain.

I was raised by a Roman Catholic father and a Baptist mother. There was also a strong Jewish influence. There was a political divide of Democratic, along the lines of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy, and Republican, with the Eisenhower/Nixon lines. On the Protestant side, there was a strong evangelical influence that, among other doctrines, insisted on the international propagation of faith. What was unclear was what defines a true evangelical Christian. Billy Graham, for example, avoided offering a definition. I find there is a diversity of opinions and definitions across the spectrum of Christian denominations.

Equally difficult to define is the word patriot. Are those who march for civil liberties any less patriotic than the men and women who join the military, or go into government service? Are Black people, Latinos, Jews, Chinese, Indians, Muslims and other nationalities living in the States any less American than whites because of their heritage and religious traditions?

The Jim Crow revival tent has been opened by the Christian nationalists who advocate banning synagogues, mosques and temples and executing heretics and apostates. They uphold the cruelest values of the Confederacy, and deny the civil rights, and voting rights of others. In their opinion, a woman’s place is in the home barefoot and pregnant. Their words are the venom of hate, and reject the Christian Gospel they say they proclaim. Oddly, their sermons rest upon the freedom they are granted by the Constitutional rights they would deny others.

My father taught us a valuable lesson on that trip through the South. He summarized this in something he oft repeated. “A man is a man until he proves himself otherwise.” In other words, the dignity of others, regardless of their race, creed, gender, sexual orientation, and religion is to be respected. He expected nothing less of himself, or his sons.

Image: Sign from segregated railroad station

Source: Exhibition: Defending Freedom, Defining Freedom: The Era of Segregation, 1876-1968

Part of Open: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

Leave a reply to Maynestay Cancel reply