When I first took up painting with the encouragement of the Canadian artists Terrill Welch and her husband, David Colussi, Terrill advised me to include notes on my sensory experiences when sketching a scene. These notes would include the time of day, temperature, sounds, wind or breeze direction, aromas, and other elements I observed. These notes, combined with the observed object(s), would enhance the scene when selecting hues for the palette.

There are times when I stare at the sky for prolonged periods and notice its diverse, subtle hues of blue and refined shades of gray. Leaves may share a commonality of a species of a tree, but have their own expression of individuality on a branch. Sunlight weaves through the tree limbs, casting pronounced color differences and silvery tints, understated as they may be. No two flower petals are alike, nor are two peas in a pod. Nature endows each created thing with a distinct character.

Among my favorite paintings is Andrew Wyeth’s Trodden Weeds. This 1951 self-portrait shows Wyeth from the knees down in a pair of old high boots that had belonged to the American artist Howard Pyle. Pyle was Andrew Wyeth’s father, N.C. Wyeth’s art teacher. The painting is remarkable in many respects. If you carefully examine the painting, tempera on panel, you will notice the careful abstraction of the weeds, their individual movements, besides the wear of time on the boots, and the action of light.

Terrill’s emphasis on my learning this lesson of observation and note-taking is summed up in the word immersion. There are natural geometric lines in our environment that guide our eyes, allowing for deeper experiences. Translating those lines and colors of our sensory experience is a lifetime of learning. Failure in articulating the sensory and spiritual moments to a canvas, whether in a plein or studio painting, is a teaching moment, thus a success if I learn from it.

How to find charm and freshness, but more importantly distinction is a concern, but an artist must do so on his or her own terms with sincerity. They must deal with what is real, visible, and imagined. The French realist painter Jean Désiré Gustave Courbet wrote to his student, “The beautiful is in direct ratio to the power of perception acquired by the artist.” Something else is required of an artist.

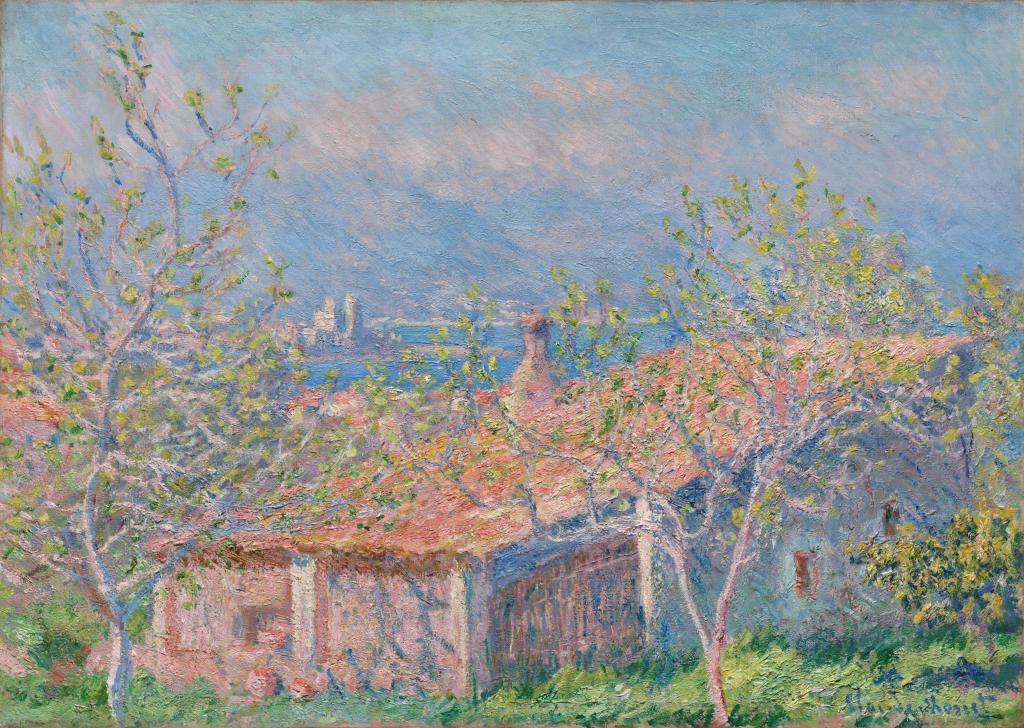

In 1877, Claude Monet exhibited 30 paintings. Charles Bigot, a French journalist and educator, wrote that Monet revealed nothing of himself, that the paintings had “no subtlety of impression, no personal vision, no choice of subjects to show you something of the man and something of the artist. Behind the eye and hand, one looks in vain for a mind and soul.” This critique surprises us, for we think of Monet as a master whose brush captures our imagination with his different effects. We see a movement of modern life along the Boulevard des Capucines and the chaos of Gare Saint-Lazare, to the façade of Rouen Cathedral, to Le Bassin aux Nymphéas, Giverny. We are witnesses to his evolving interests, the changing techniques, and he is always asking us, “What caught your attention?”

Time and light are the most difficult aspects of painting. Light travels at a constant speed of 186,000 miles per second. Simultaneously, while making their observations, the artist is stationary, even as their eyes and hands move; the light is in constant motion. Monet remarked on his The Meule Series, “For me, a landscape does not exist as landscape, since its appearance changes at every moment, but it lives according to its surroundings, by the air and light, which constantly change.…”

When you examine The Meule Series, you notice the stacks of hay in the field. A casual glance reveals a mundane scene of distant hills, a few houses. When we take moment to closely examine the scenes, we discover seasonal changes displayed from one day to the next. The hay stacks are mirrors capturing the mood of the surrounding environment. The light and shades are relentless. There are sudden glows of color as the sun pursues its course. In the sunlight, you feel the drying heat, the frozen snow, the dampness of the hay after a rain storm, and the mist. There is a harmony of movement, a warmth of colors. The paintings depict earth veiled in the timid warmth of spreading sunlight and evening shadows descending over it. The haystacks are both a celebration of autumn, melancholy, confusion and grief of waning daylight as winter descends across the field. The landscape has given Monet everything to comment on life.

Time is always present; it is always an open invitation to observe, to open our eyes to see, to allow our senses to experience the fleeting moments of what is before us, and it demands we be present to the flickering passage of time.

Each of us brings a unique perspective to life. We live in front of canvases, not to record data, but to make our lives valuable, to experience something more than materialism, to create something valuable, a sense of time as duration and memory, that, in the words of the French philosopher, Henri-Louis Bergson, “by allowing us to grasp in a single intuition multiple moments of duration… frees us from the movement of the flow of things, that is to say from the rhythm of necessity.”

“What does a canvas teach you?” is a question I often mentally hear Terrill asking me at every stage of creating a painting, from preparing a canvas to the last brushstroke that completes the piece. The correct answer lies in how to be awakened to life, how to find the truth in what I am seeing.

__________________________________________________

Painting: Gardener’s House at Antibes

Artist: Claude Monet

Credit Line

Repository

The Cleveland Museum of Art

Cleveland, Ohio, USA

Collection: Mod Euro – Painting 1800-1960

https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.24558656

Artstor

Leave a comment