The Times published a poem by Robert Palmer in 1916 that reads in part:

From sodden plains in West and East the blood

Of kindly men streams up in mists of hate,

Polluting Thy clean air: and nations great

In reputation of the arts of that bind

The world with hopes of Heaven, sink to the state

Of brute barbarianism whose ferocious mind

Gloats o’er the bloody havoc of their kind,

Not knowing love or mercy.

Palmer’s poem was published three months before his death at the Battle of Hanna, 21 January, 1916.

There is a story about a hospital ship on the Tigris the historian Martin Gilbert recounts about a Second Lieutenant “looking at the torment of those wounded who had been brought on board, but for whom, even there, no medical help was forthcoming, is said to have remarked to his sergeant: ‘I suppose this is as near hell as we are likely to see?’ Drawing himself up, as in answer to a parade-ground question, the sergeant replied: ‘I should say it is, sir.’”

When I look back on history, I find that no government or group has a moral argument for starting a war. If there is any justification, it is in resisting aggression. I am wary of those political leaders, mostly civilian, who claim to be protecting their national interests and yet act belligerently toward another sovereign nation. The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the U.S. military actions towards and in Venezuela are nationalistic actions and criminal. The recent 10-hour live-firing naval and air force exercises by the Chinese Communist Party around Taiwan, according to the Chinese military’s Eastern Theater Command, are intended to test “sea-air coordination” and “integrated containment capabilities,” which bring China closer to committing an act of aggression. Similar aggressive activity by China is observed in the South China Sea around the Philippines.

The prevailing attitude towards war in the Trumpian Age is reminiscent of the “little wars” of the 19th century for territorial gains, natural resources, and political influence. Those wars, and this is a short, partial list, include the Crimean War of 1854-6, the 1839-41 “Opium War,” the 1897 Greco-Turkish War, the Boer War, 1899-1902, and the 1898 Spanish-American War. For the victims, there was nothing “little” about these wars. These wars culminated in the outbreak of the Great War of 1914-18. In the first 25 years of the 21st century, 54 of the 194 nations have been engaged in war. Many of these remain ongoing.

There are advocates of war who believe they are acting defensively and hold a deep conviction in the justice of their cause. However, even their best intentions for justice can distort the consequences of war. Geoffrey Claussen, a professor of religious studies at Elon University, writes:

“Equanimity and justice are among the virtues that those deciding on matters of war policy should regularly assess. A number of the other virtues highlighted by Menaḥem Mendel Lefin would also seem to merit particular attention. Among them is a virtue translated as “diligence” (ḥaritzut), an appropriate sort of decisiveness which is neither overly hasty nor overly cautious; Lefin stresses caution, but also stresses that one must train oneself to arrive at rational decisions and act on them with relative speed. Honesty is another key virtue, discussed in numerous places: a policymaker must be honest about the realities of war, honest about his or her claims to be on the side of justice, honest about the limits of his or her knowledge, and honest about his or her biases and interests.”

Training in rational thinking, caution, and honest discussion of what applies to both the development of a defense policy and the implementation of the policy during a crisis― a real, not a fabricated crisis.

This understanding is absent from the rhetoric of the Trumpian Age, particularly when directed at Venezuela, Iran, Gaza, and Ukraine. Instead of terms such as honesty and patience, which are used in reasoned, ethical debate, the president and Secretary of War (as he prefers to identify himself) use terms such as “warriors,” “fog of war,” “destroy,” “be killers,” and “fury.” For this Administration, war is about power politics and “the art of a deal,” and gunboat policy, which has nothing to do with genuine peace.

The Trump Administration’s military operation in Venezuela, and Trump’s announcement that the United States would run the country, are a violation of both U.S. and international law, according to many legal experts. As Senator Jack Reed has stated, “No serious plan has been presented for how such an extraordinary undertaking would work or what it will cost the American people. History offers no shortage of warnings about the costs – human, strategic, and moral – of assuming we can govern another nation by force.”

I was privileged to attend a meeting with President Gerald Ford, the Director of Central Intelligence, and former DCIs, National Security Advisors, and military leaders from previous administrations. The discussion focused on the policies behind past and potential military actions, the strategies for those actions, and the consequences of their decisions.

Among the specific issues discussed at length was whether further intervention in Iraq following the Gulf War was a matter of national security. At that time, al-Qaeda was just beginning to emerge as a global terrorist threat. How do we respond? Did we have all the intelligence to make the right decisions? Were there better options besides war? How could justice be established for the Iraqi people? What was the exit strategy? Was the United States getting involved in nation-building? Casualties among our personnel and the civilian population were taken into account, as were concerns about potential violations of International Humanitarian Law and International Human Rights Law. Chest thumping, politics for self-gain, or intent to distract from troubled domestic policies, and “the art of a deal” were absent from the conversations.*

As I listened to the discussions and the responses to my questions, I came to realize that those in leadership who had experienced combat lacked a taste for war, except as a defensive measure against aggression. Their attitudes now bring to mind lines from Philip Parotri’s short story “Urns of Ash.” He writes;

“Therefore I advise you to negotiate, negotiate and make peace, for if you do not, Lords, you have no other choice but to prepare urns, and the ashes of misery will follow.”

________________________________________________

*Note: A consensus was reached that further military action was ill-advised and not warranted against the Hussein regime. The advice was passed on to the then-current administration. Regretfully, the next administration ignored it. They and two subsequent administrations followed a disastrous course. At the same meeting, there was a consensus that Al-Qaeda warranted a different response, but one that would not involve assassination. The material reviewed in that meeting was declassified.

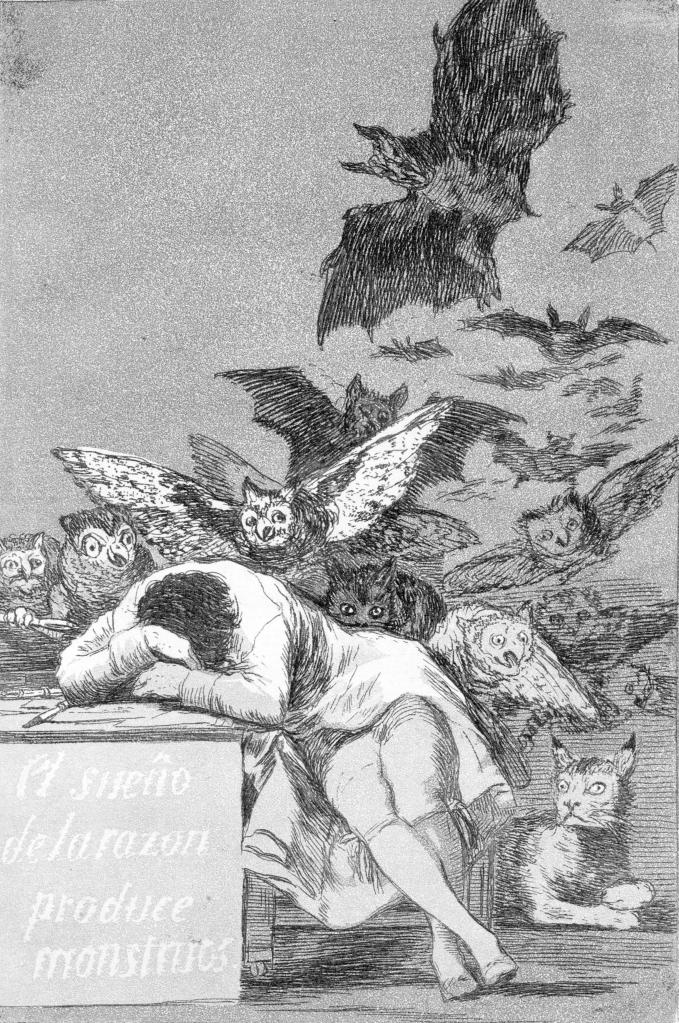

Illustration

Title: Plate 43 from “Los Caprichos”: The sleep of reason produces monsters (El sueño de la razon produce monstruos)

Artist: Goya (Francisco de Goya y Lucientes) (Spanish, Fuendetodos 1746–1828 Bordeaux)

Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Drawings and Prints Gift of M. Knoedler & Co., 1918

https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.1867441

ArtStor

Leave a comment