The summer of 1966 was a difficult time for me. In the spring, my father had died suddenly. My mother had decided I should attend Boy Scout camp for a week. In the weeks leading up to it, I had been staying with the Hingstman family in Vestal, New York. I was uninterested in attending camp and would have preferred to go from the Hingstman home to my grandparents in Richburg, a few hours away.

The troop’s adult leadership hired a college student to attend to us; some of the boys would be there for two weeks. I am unable to recall either the counselor’s name or whether he was an undergraduate or a graduate student. What I do remember is his kindness towards me. I lacked interest in the camp activities. Seeing how withdrawn, confused, and in grief I was, he reached out. For some reason, our first conversation ended with him loaning me a book on Greek philosophy. While the other boys swam, played baseball, and took part in various programs, I sat in the shade, reading about the Greek philosophers. In the evenings, the counselor and I sat outside his quarters discussing the book. I think he was surprised by a 13-year-old’s appetite for Greek thought. The one character that impressed me was Diogenes of Sinope.

Diogenes (c.400 ― c. 325 B.C.E.) was in exile in Athens. There are anecdotes about him, his life of extreme poverty; he may have written tragedies and dialogues, but he became a legendary figure after his death, and his caustic wit influenced later writers. Happiness, Diogenes reasoned, is attained by satisfying one’s natural needs in the cheapest and easiest way. Another principle was that what is natural can neither be dishonorable nor indecent. This latter point often ran counter to societal conventions; he was often crude in his behavior, resulting in considerable trouble for him. Perhaps it was his oddity that attracted me. He was willing to swim against the tide― not with the school of fish.

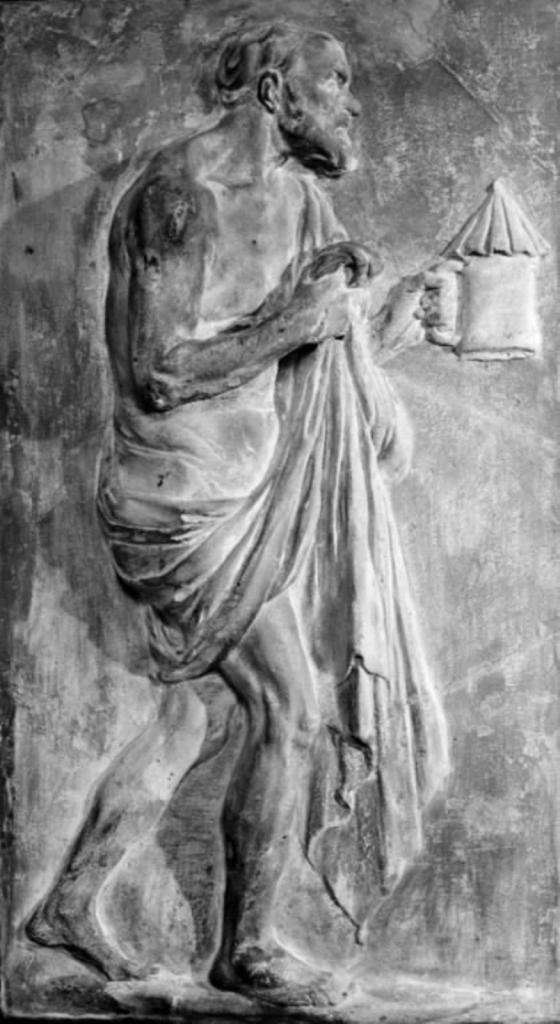

One story attributed to him has remained with me over the years. The apocryphal story tells of Diogenes walking the streets of Athens carrying a lantern in broad daylight. Someone stopped him, inquiring why the lantern. Diogenes responded, as Dr. Leon R. Kass observes, “I am seeking a human being (ζητῶ ἄνθρωπο) — anthrôpon zeto — can be translated as either a human being or the human being, or as either an exemplar of humanity or the idea of humanity or both.” This is a remarkable statement that, upon first reading, still gives me pause.

What does it mean to seek a human being, or to be an exemplar of humanity?

In Yiddish, the term mentch is commonly understood to denote a decent, good person who is considerate of others. However, as Kass reminds us, to “be mentschlich is to be humane… but it is also to be human, displaying in one’s own character and conduct the species-specific dignity advertised in our uniquely upright posture. Mentschlichkeit, “humanity,” the disposition and practice of both “humaneness” and “human-ness… personal integrity and honesty, self-respect and personal responsibility, consideration and respect for every human person (equally a mentsch), compassion for the less fortunate, and a concern for fairness, justice, and righteousness.”

The Bible has two Hebrew words for justice. Mishpat (מִשְׁפָּט) meaning judgement/justice. This is the application of the law, ordinances, and legal rulings, and the implementation of fairness. In the Tanakh, Tzedek (צֶדֶק ) translates as righteousness/justice. This refers more to what is right, fair, and kind, and involves compassion and giving. Tzedakah is righteous behavior to fulfill the will of God. It does not imply self-righteousness. To state this another way, Tzedek denotes the inherent righteousness and fairness of an act. Mishpat, by contrast, refers to the manner in which righteousness is applied and upheld in society through systems, laws, and human actions.

In the Book of Jeremiah (5:1) we read that the prophet was called to:

Run to and fro through the streets of Jerusalem,

look and take note!

Search her squares to see

if you can find a man,

one who does justice

and seeks truth...

This verse always reminds me of Diogenes.

The Book of Jeremiah is my favorite of the prophets. He is an anchor of hope and promise, intent on saving the people while rendering judgment (i.e., Jeremiah 1:10). He has sympathy for both God and humanity. He pleads for both. He is a person of deep sensitivity, gentle and compassionate, who performed a task he found displeasing.

In chapter 22:13-19, Jeremiah rebukes King Jehoiakim for being concerned with expanding his palace rather than giving justice to the poor and needy, and acting righteously. Those words thunder against the policies and greed of the Trump Administration. But I digress.

Although the prophet and the philosopher are distinct in personality and motivation, both are complex and stand by their convictions.

To be humane, to have "the disposition and practice of both "humaneness and "human-ness" is difficult in the Trumpian age, when even on the brightest of days, there are shadows of darkness― anger, fear, and doubt. However, what is difficult is not impossible. Our ethical behavior, as Aristotle reminds us, are, in Kass’ words, “acts for the sake of the noble, for the sake of the beautiful."

Unlike Diogenes, we do not need to carry a lantern searching for a human being. If we allow ourselves to follow our scriptural and humanistic traditions, then we become the light to others, just as that college student was to a grieving boy sixty years ago, and so many others have been since.

Image 1: Diogenes med lygten

Creator: Jacques François Joseph Saly

Date: 1740-1746

Source: Image and original data from Statens Museum for Kunst

https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.28365987

Image 2: Jeremiah. Chromolithograph by Storch and Kramer after C. Mariannecci after Michelangelo.

Source: Image and original data provided by Wellcome Collectionhttps://www.jstor.org/stable/community.24905378

Leave a comment