Words are often used with little thought to their meaning. Finding the right word to describe someone or something requires observation and thought. The context of what we are witnessing and how we intend to convey the observation, and to whom, requires consideration. Finding the right word is comparable to attaching weights to a fishing line. The weights used depend on the type of rod, your technique, the line’s strength, the environment (ocean, lake, or stream), and the fish you hope to catch, among other factors. The same applies to selecting words.

Writers fish for ideas. The fundamental questions are what, when, who, why, and how, though not necessarily in that order. Those questions pertain not only to what is going to be expressed, but also to the genre used once an idea is hooked and reeled in, and the audience that the material is intended for.

Anyone who has worked on translations knows the difficulty of finding suitable words to convey the original intent and sentiment of the author faithfully. Words can and do have various meanings from one language to another. Additionally, words often have multiple meanings. Another difficulty is that, over time, the meaning of words and how they are used frequently change.

Three classic words have been bantered about lately that require a closer look. These are revenge, vengeance, and retribution. We find them in the Bible, Greek and Roman literature and plays, Shakespeare, operas, contemporary literature, and acted out in our films, plays, and video games. These words are timeless in the drama of human life.

I have been asking myself why these words have come to define and have such a dominant influence in this particular time in American (world) history. This morning, I went to the Oxford English Dictionary to look them up. What is the difference between these words? What is the message they send? How do they influence our mental health? Then I turned to articles by psychologists for their perspective.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines revenge as “the act of doing hurt or harm to another in return for wrong or injury suffered; satisfaction obtained by repayment of injuries.” A second definition is “A desire to repay injuries by inflicting hurt in return.” Vengeance is defined as “the act of avenging oneself or another; retributive infliction of injury or punishment; hurt or harm done from vindictive motives.” Retribution is defined as “punishment inflicted on someone as vengeance for a wrong, real or perceived, or a criminal act.”

The author, Dr. Bernard Golden, writes, “Revenge is personal, powerfully driven by emotion. The motivation for revenge might be initially fueled by anger, but it is ultimately powered by anticipated satisfaction or enjoyment. A powerful driving force for revenge is the belief that acting out the desire for revenge will provide an emotional release, that it will help us feel better. However, studies have found that while there may be initial satisfaction, revenge actually perpetuates the pain of the original offense. Additionally, it often creates a cycle of retaliation, with the victim citing the most recent offense as yet another justification for further revenge. In effect, revengeful feelings and behaviors only train the brain to become more vulnerable to seek revenge.”

There is satisfaction in revenge. For some, it is a way to restore balance to the universe. You, the offender, made me suffer; now I will inflict suffering on you. This is known as “comparative suffering.” The second theory is known as “the understanding hypothesis.” In this, satisfaction is found when, as the author Eric Jaffe observes, “the offender’s suffering is not enough on its own to achieve truly satisfactory revenge. Instead, the avenger must be assured that the offender has made a direct connection between retaliation and the initial behavior.”

Can we continue to accept the idea of being governed by “revenge and retribution”? Is revenge so deeply ingrained in human nature, as our literature suggests, that we perceive it as a means to achieving justice and self-healing?

Politically and socially, we are in a time when “revenge and retribution” are the standard operating procedure. As I read the psychological articles, I am reminded of Francis Bacon, who wrote, “A man that studieth revenge, keeps his own wounds green, which otherwise would heal, and do well.”

In Avot-de Rabbi Nathan (chapter 23), we find, “Who is it that is most mighty?” with the response, “Mighty is the one who makes an enemy a friend.”

We must not allow the sweeping desire for “revenge and retribution” to, in the words of the Jewish liturgical scholar, Eric Friedland, “impair our ethical style and sensitivity. We must not lose our moral and spiritual temper as a goy qadosh, a holy people.”

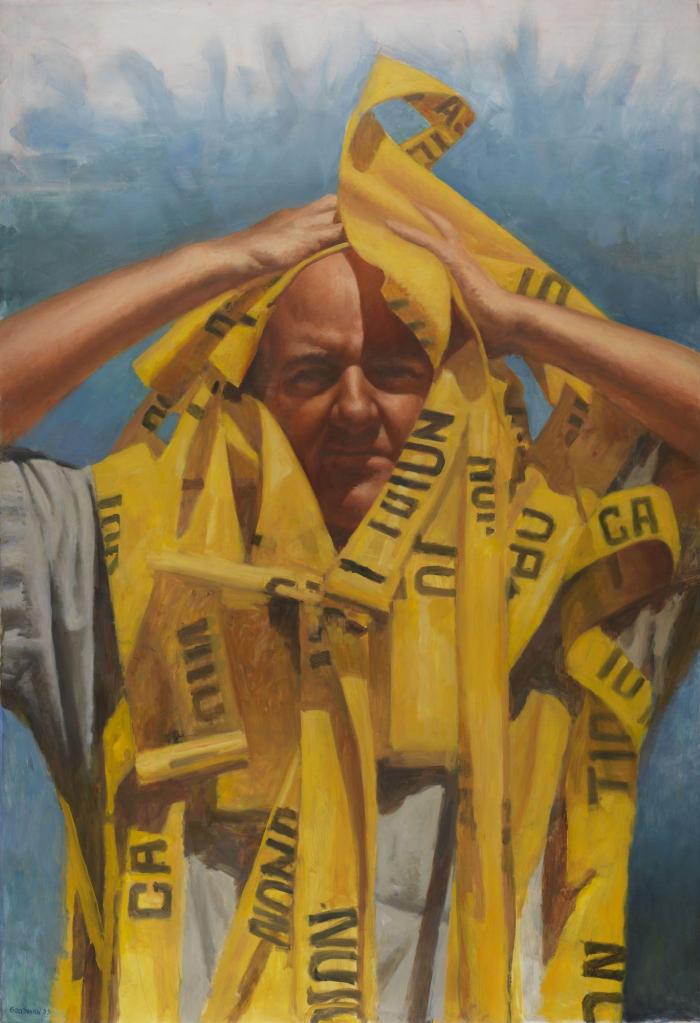

Image: Self-Portrait with Caution Tape

Artist: Unidentified

Rights Notes

© Estate of Sidney Goodman / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

This item is being shared by an institution as a part of Shared Collections.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.38265003

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts PAFA

Leave a comment