Hats are both a fashion statement and an expression of identity. Women of the British elite are known for their hats. Appearing hatless at the Kentucky Derby is taboo for American women—fashion matters.

A hat is a persona, revealing either who we are or who we want others to think we are. Hats also express the groups we identify with. Wear a team baseball cap, say the L.A. Dodgers, or the Boston Red Sox, and people rightly assume you are a fan, part of the clan. MAGA hats make both an identity and a political statement. Hats have been in decline since 1928, when college students began dismissing the fashion trend and went hatless. The sale of hats declined after World War II. Contrary to popular mythology, John F. Kennedy wore a top hat on the frigid morning of his inauguration. Afterwards, Kennedy seldom wore one.

I have a few hats. The Marine Corps hats, gifts from cousins, are hung on the wall along with one hat with the patch of the 810 Tank Destroyers that my uncle served with during the Second World War. There is one Navy cap. These hats aren’t worn. They serve as reminders of the sacrifice of others.

My other hats vary from Irish driving caps, a tweed walking hat, an Australian outback hat, and a few plain (minus logos) baseball caps, though two bear the names of the colleges my daughters attended. My hats are vintage and well-worn. I prefer clothing that isn’t an advertisement for a company or a tourist destination.

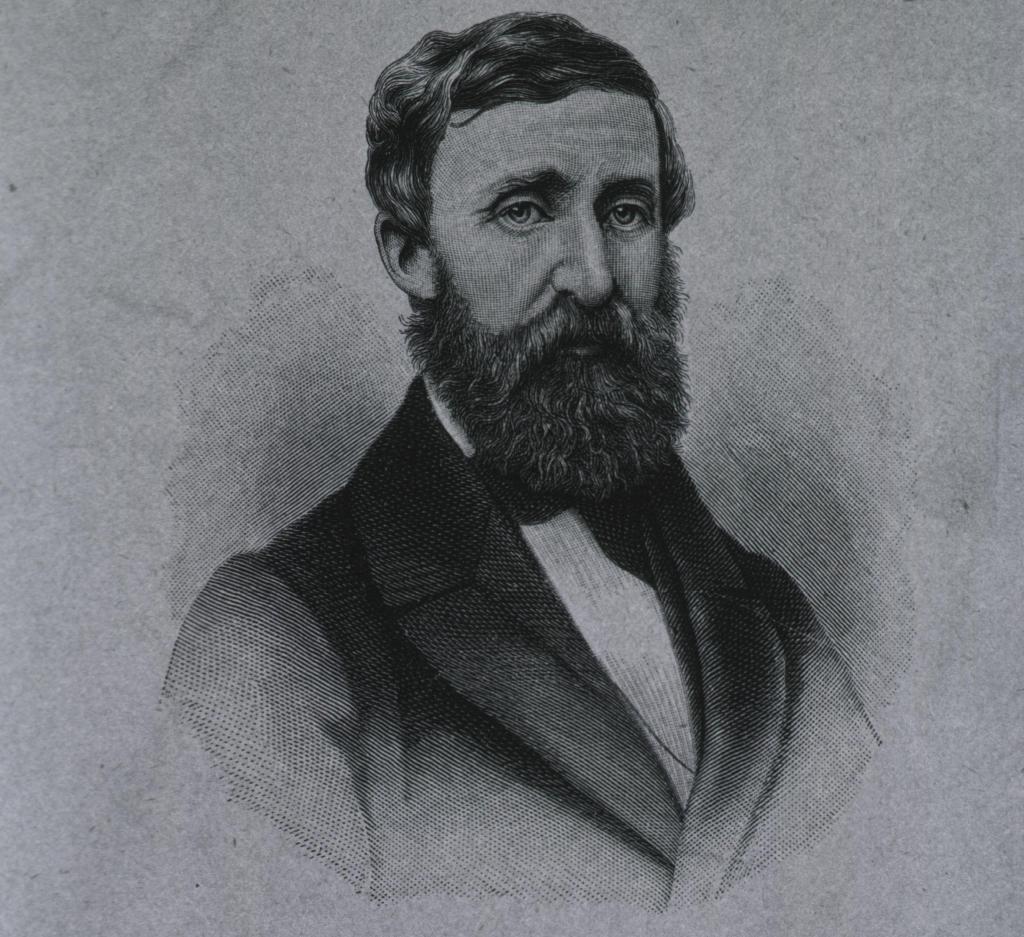

I began thinking about hats the other morning while reading an article written by Tony Luong about Richard Smith in the New York Times (Sept. 13, 2025, Section A, Page 1 of the New York edition with the headline: On Walden Pond, Hanging Up His Frock Coat.). Smith is a historian and writer. Since 1999, he has been impersonating Henry David Thoreau at Walden Pond, educating students and other groups about “Thoreau’s experiment in living simply.”

Impersonating Thoreau, or anyone else for that matter, sounds easy. Luong notes a few of the difficulties of wearing Thoreau’s straw hat when he writes:

“The gig had its challenges. Besides having to wear an itchy frock coat on sweltering summer days and forcing himself not to utter contractions, the job meant setting some Thoreau fans straight about certain things. He was not a hermit, for one thing. The cabin on Walden Pond was near train tracks, and he often visited his family in town, where his mother did his laundry for him.”

Smith’s portrayal is a reminder that Thoreau’s experiment was to “live deliberately.” What does this mean? Margot Wieglus observes that deliberate is used as a verb by Thoreau to “denote a kind of thinking… to deliberate is ‘to engage in long and careful consideration.’ The secondary meaning indicates that living deliberately may also be interpreted as carefully considering how to lead one’s life.”

Do we go about life with thoughtful deliberation? We live in a consumer-driven society. Are the goods that we purchase the absolute necessities of life? How much time do we spend earning sufficient money to buy and maintain those items? Are those values for a way of life limiting us to pursue other possibilities for better living, both spiritually and wakefully in purpose? As Thoreau notes, “… we must learn to reawaken and keep ourselves awake, not by mechanical aids, but by an infinite expectation of the dawn.”

Each day is unique, offering new possibilities. This is not to deny difficulties and “unpleasantness.” But what do we learn from those times of trouble, difficulty, frustration, pain, suffering, and loss? These are, along with peaceful, joyful, pleasant times, an aspect of our growth as individuals that deepens our self-awareness and aids us in exploring and discovering sincere and “deliberate” living.

Luong writes of Richard Smith, “As Thoreau, he has spent quiet days in the solitude of the one-room cabin, with its wood-burning stove, straw mattress and plain writing desk, often stepping outside to contemplate nature.”

Do we allow ourselves that time of solitude, to “step outside to contemplate nature”?

Nature, the seasonal changes, reminds us that our lives are transitional. Each day, as well as multiple times throughout a day, we wear various hats. Do we allow ourselves time to remove the persona of our hats to reflect and mature, to contemplate, embrace, and learn from the new dawn of each day? Do we take the time to consider and question everything from the blossoming, delicate flower to the rules and schemes governing our lives?

I disagree with various aspects of Thoreau’s philosophy. Yet there are aspects of his thinking that, in these turbulent times of anger, hate, and unconscionable violence, his voice is one among others that is needed to understand our societal relationships, our place, and our connection to our earthly environment, and to ourselves.

On 6 September, Richard Smith removed his straw hat for the last time. He retired from his portrayal of Henry David Thoreau. He will focus on his own writing. And I suspect that like Thoreau, he will climb a tree and discover “new mountains in the horizon which I have never seen before.”

Image: Title Henry David Thoreau

Sources: Repository U. S. National Library of Medicine (NLM) from the History of Medicine

Local Identifier: 101430524; IHM: B08957

Leave a comment